A simple yet thorough AI explainer

A deep-dive on how AI works to an entirely non-technical audience.

Over the past few years, it seems like magical new AI models are being conjured into existence on a daily basis. These new models can do things that were previously thought impossible for computers: writing poems, creating award-winning images, making music, producing cinematic videos, the list goes on and on.

We are used to magical technologies in the 21st century. You can talk to someone from the other side of the world, take little white pills that make your pain go away1 and use a flushing toilet while flying thousands of meters above the earth's surface. But deep down, you know that these things are not really magic, you can peel back the layers and figure out how each of them works.

These new AI models feel different. It no longer seems like you're interacting with a computer. You simply ask them what you want in natural language and out comes a human-like response. On top of that, these models have an extremely wide range of capabilities and even the engineers who created them are sometimes surprised at what they can do!

In this article, I am going to dispel some of the magic surrounding AI. I won't be focusing on specific types of models, like large language models (which power ChatGPT) or diffusion models (which power image generators like Midjourney). Instead, my aim is to provide you with an intuitive understanding of the principles behind AI, which aren’t so difficult to grasp if they are explained properly. It’s like rockets. Everyone knows how they work in theory2, it's the nitty-gritty details of rocket engineering that's the hard part. The same goes for AI.

AI is weird

One of the reasons people misunderstand AI is that it looks and feels like all of the other digital technology in our lives. We use the same devices, the same interaction patterns and even the same design systems as traditionally coded apps and products. Because of this, our intuition tells us that we are dealing with an improved version of existing apps, when in fact, AI models work completely differently behind the scenes.

Traditional code is like clockwork. You provide some input, it is processed in a logical manner, following the exact steps defined by its developers and out comes a predictable response. If there is a bug, it's because one or more of these steps haven't been defined properly and you can just look at the code to figure out why it isn't working the way you expect.

The tasks we have managed to do with computers so far have all revolved around things where it was more or less easy for us to give specific and precise instructions.3 Multiply 8234 x 3289 ? Easy. There is a logical step-by-step process for that. Write a poem about multiplying 8234 x 3289 in the style of Shakespeare? Step 1. Uhhhhhh... become Shakespeare?

This is where AI comes in, it can write a poem about multiplying 8234 x 3289 in the style of Shakespeare, and it can do so precisely because it doesn't work in a logical step-by-step manner.

AI models are statistical and make predictions instead of providing definitive answers. They don't have a process for calculating outputs, only a kind of 'intuition' for what the answer might be based on patterns they learn during training. This is why they often ‘hallucinate’ and are bad at math. And unlike traditional code, we can't peel back the layers of the model to identify what these patterns are or how they are being used to calculate a response. To understand why, let's start by exploring what the inside of an AI model actually looks like.

The building blocks of AI

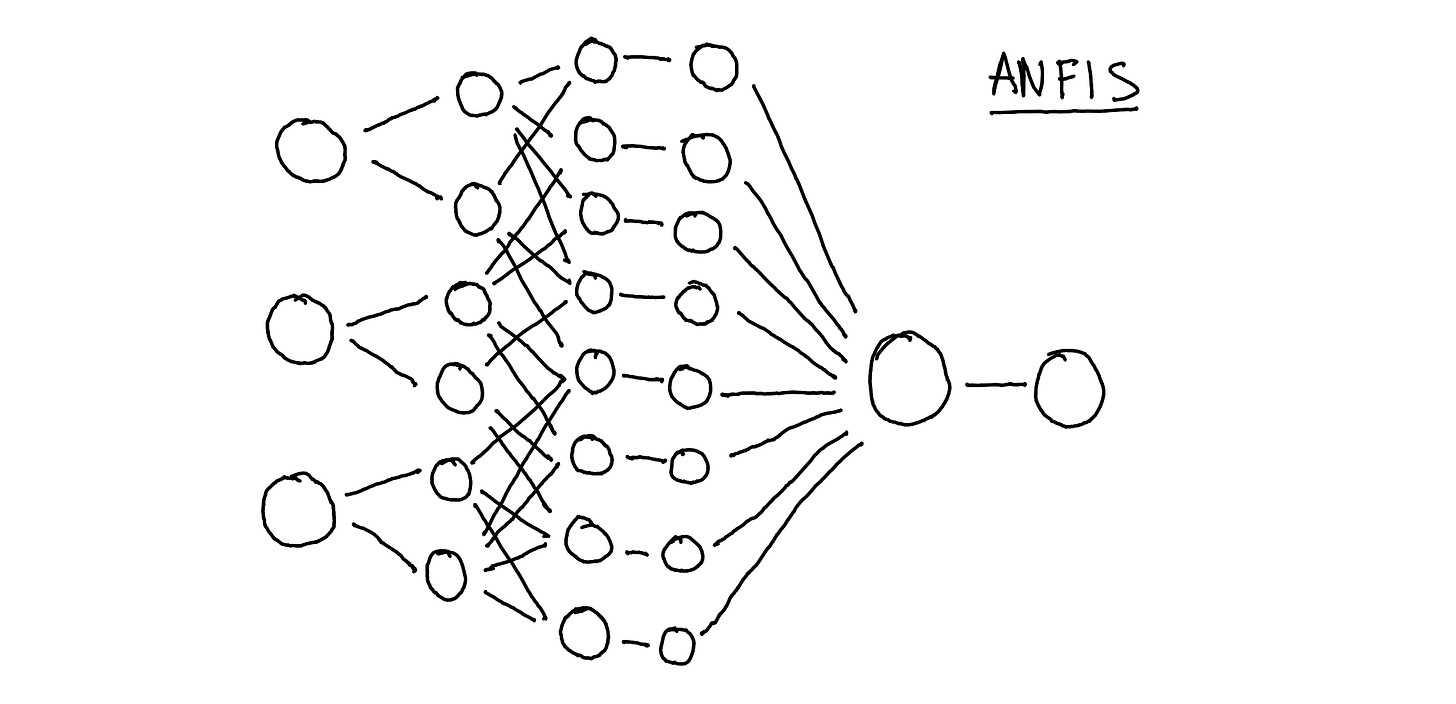

When you google "structure of an AI model", you get lots of diagrams accompanied by acronyms that look like a cat walked across you keyboard.

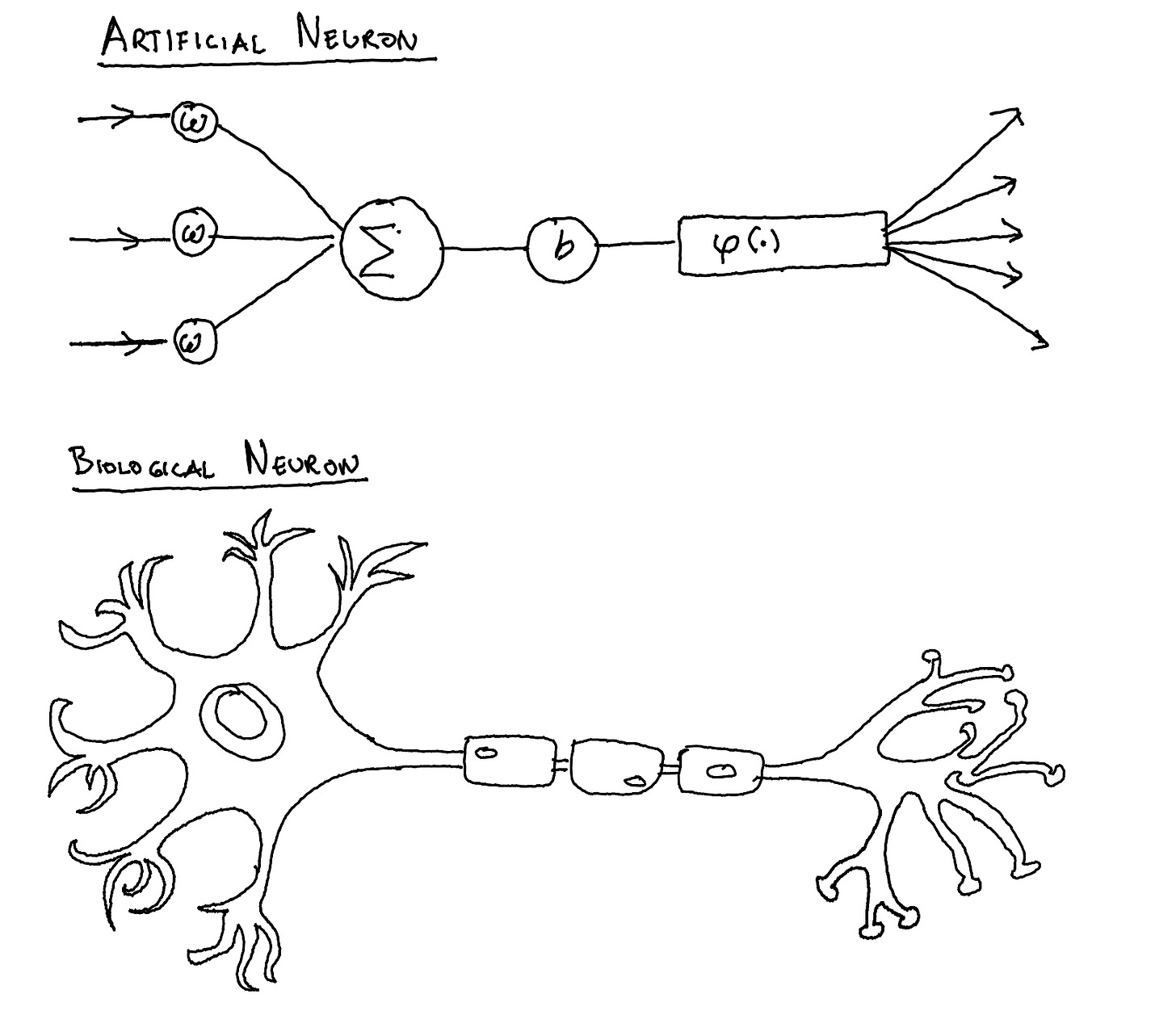

These diagrams show the ‘architecture’ of an AI model, and explain how its put together. A model is made up of lots and lots of numbers organized in specific ways. Small collections of these numbers are grouped into 'neurons', and form the basic building blocks of AI.4 Most AI models today are known as ‘neural networks’, since they’re essentially just thousands, millions, billions or even trillions of these neurons connected together. The way they interconnect, which is what the diagram above is showing, determines what a neural network is capable of.

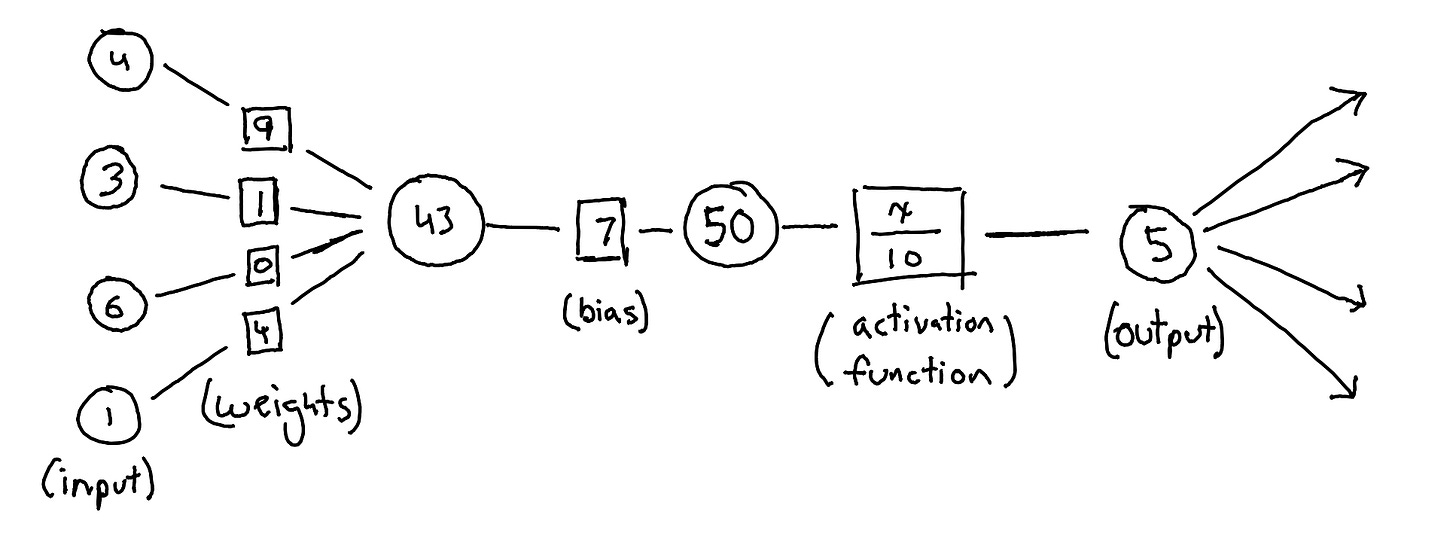

The job of each neuron is to take the inputs coming in from other neurons, transform them using a set of numbers, and pass the result (output) along to the next set of neurons. It does this by multiplying these inputs with another set of numbers (called 'weights'), summing all of the results, adding another number (the 'bias'), and finally running this number through an 'activation function' to get the output. Let's walk through it step-by-step using the following example.

The neuron receives inputs. (4, 3, 6, 1)

Each input is multiplied by its own unique weight, each one with a different value.

4 x 9 = 36

3 x 1 = 3

6 x 0 = 0

1 x 4 = 4

The products of each weight and input pair are added together. (36 + 3 + 0 + 4 = 43)

The sum is then added to the bias. (43 + 7 = 50)

This sum (x) is run through the activation function. (50/100 = 5)

The output (5) is passed along to the next set of neurons.

The specifics of this setup, such as its activation function, varies according to the AI model, but the principle behind every neuron is the same. Take some incoming numbers, combine and modify them to create a new number and send it along to the next set of neurons, which repeat the process. Simple!

Assembling a model

Despite their simplicity, neurons can do some incredible things when you connect millions and billions of them together. Think of them like little ants that are part of a giant colony. A single ant by itself can’t do much, but thousands of them together can build some of the most elaborate structures in the animal kingdom.

The role of these millions and billions of neurons in an AI model is to transform some input data into the ‘correct’ output data. What that data is depends on what the model was setup to handle by its engineers. It could be images, text, audio, pretty much anything we can represent using numbers.

Neurons are organized into layers, where each layer is a step in the process of how the data gets transformed as it moves through the model. The first layer of neurons acts like a sensory organ, converting data into numbers that the rest of the model can work with. There are ‘ears’ for processing audio, ‘eyes’ for processing images, etc. Each model is equipped with a different set of these ‘organs’ depending on the data it’s meant to handle. You can't sing into an image classifier, for example, since it doesn't have 'ears' to be able to 'listen' to audio. It's first layer was designed to handle images, not your drunk rendition of Bohemian Rhapsody.

Similarly, the final layer converts the numbers output by the model back into a form that we can understand. The neurons in the output layer are mapped to specific pieces of data that you want the model to be able to recognize or generate. An audio classifier with 500 neurons in its output layer can classify audio across 500 different text labels. An image generator with 7500 neurons in its output layer can create a 50px by 50px RGB image (50 x 50 = 2500 pixels, multiplied by 3, so you have one neuron for each color channel per pixel).

The neurons between the first and last layer are responsible for transforming the converted input into the output. Here's a high-level view of the whole process.

The model is given some input data.

This data is converted into a series of numbers by the first layer.

These converted numbers are passed into the next layer of neurons, which transform them into a new set of numbers, using the mathematical process described earlier.

The outputs of this layer are then passed as inputs to the next layer of neurons and the process repeats over and over again through all of the layers of the model until we get to the output layer.

The output layer takes the final set of numbers and converts it back into human-readable formats like text, image etc.

At each step of this process, neurons are transforming their inputs into outputs using the values of their weights and biases. If we change the values of these weights and biases, how the data gets transformed also changes. The trick is to find the right values for the weights and biases within each neuron so that data is transformed in the 'right' way. And how exactly do we do that? Through training!

How to train your pet AI

The word 'training' is usually reserved for things like sports, where you practice your skills over and over again, getting better with each repetition. Or for training your dog, where you give treats to reinforce good behavior and punish them for bad behavior so they eventually do what you want. An AI model is trained in exactly the same way, using a process of repetition and rewards to refine its weights and biases until it can transform data correctly.

When you train an AI model, you're saying something like, 'whenever you see an input X, I want you to produce an output Y,' over and over again, for all of the various combinations of Xs and Ys you want the model to ultimately be able to produce. These example inputs and outputs are known as a model's training data and it's one of the biggest factors in determining its capabilities.

Your training data should represent the type of tasks you want the model to do in the real world. If you want an image classifier to recognize images of dogs, you need to show it some images of dogs. If you want a large language model to role-play Socrates, you want to include his writings as part of your data set.

Collecting and curating these data sets can be a lot of work. You have to make sure all of the data is labeled correctly, is representative of the type of outputs you want from the model, and is free from unwanted patterns (such as racial bias). There are some well-curated public datasets, like ImageNet, that offer a good starting point for developing new models. However, if you want your model to do something unique or proprietary, you typically have to collect and curate your own dataset.

Once you have your training data, you give your model example inputs and have it generate outputs. You measure how close these outputs are to the expected results and use that measurement to give the AI model a score. The closer the model’s output is to the expected result, the better the score. The goal of the model is to keep 'learning' until it gets the best score possible. Now, what does that actually mean, when we say an AI model 'learns'?

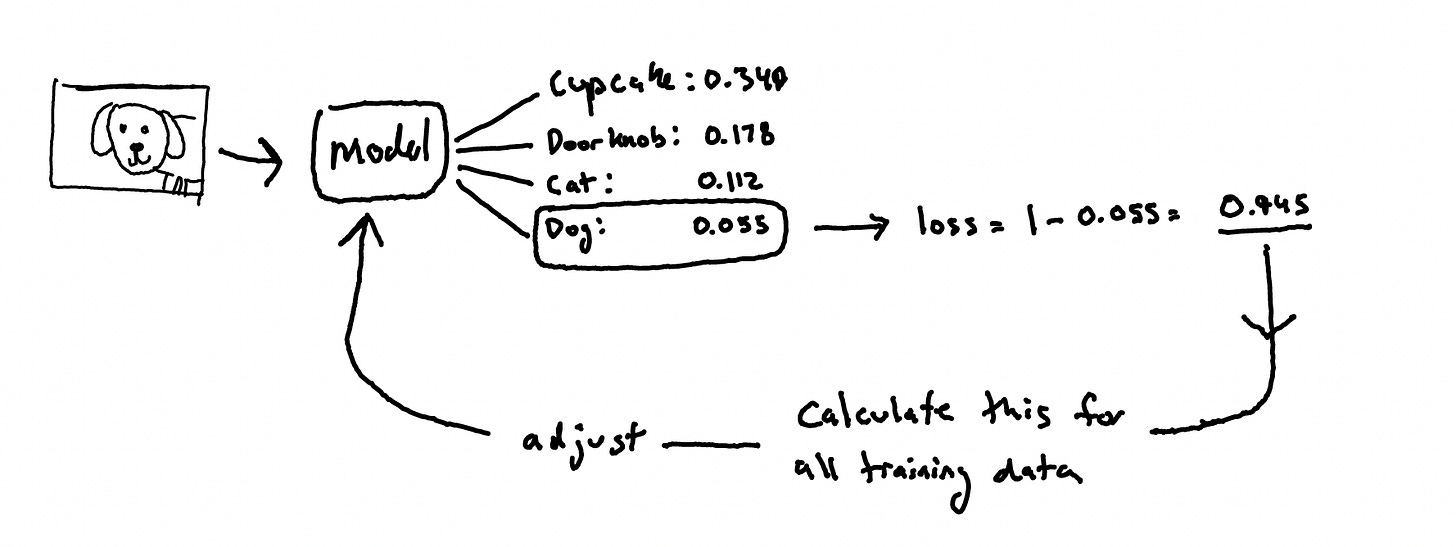

As mentioned, models are statistical, meaning that when given an input, they produce a probability for all of their possible outputs. For example, when you show an image classification model a picture of a dog, it will produce a result like { Dog: 59.8%, Cupcake: 32.1%, Cat: 5.3%, Doorknob: 2.3%, etc. }, The highest probability from this list is typically what gets shown as the final output.5

When you first create a model, all of its weights and biases are set to random values. Since the weights and biases determine how the input data is transformed, it means that when you provide a new model with an input, it will produce a random list of results from all of its possible outputs. For our image classifier, this could be { Cat: 34.9%, Doorknob: 17.8%, Cupcake: 11.2%, Dog: 5.5%, etc. }

You know that the correct answer should be 'Dog' and you can measure how 'wrong' the model is by subtracting the percentage it assigned to ‘Dog’ from a hundred percent (100% - 5.5% = 94.5% ).6 You do this for your entire training set and calculate a total 'wrongness' score, known as the 'loss'. This score shows how the current values for the weights and biases perform across all of the input and output pairs in your training data. A loss of zero is a perfect score, meaning the model was able to map all of the inputs to the correct outputs.

You can use the loss to adjust the weights and biases in each neuron in the model so that it's more likely to produce the correct output next time. This process of correction is called 'backpropagation' and its where the complex math comes in to define how much and in which direction each of the values for the weights and biases should be adjusted.7

This cycle of testing the model, calculating the loss, and adjusting the weights and biases is repeated over and over again until you are either satisfied with the output, have run out of data to train the model on, or stop seeing any improvements in its performance.

Importantly, at no point do you tell the model how to produce the right output. In fact, you can't even really see how it has produced the right output.8 You just tell it to make a prediction (or generate an image, text, audio, etc.), calculate how far away it gets from the right answer, and ask it to update itself so that its more likely to get the correct result next time.

This whole process is the equivalent of a teacher showing a student some random problems, asking them to give their best guess and telling them how wrong they are until they somehow learn how to get the correct answers on their own. For all the teacher knows, the student could be doing addition using an abacus they knitted out of their own sweater. As long as they get the correct answer it doesn't matter. A pretty shit system but somehow its the best we have for training AI. 🤷♂️

Because we can't really tell how AI models produce their output, the primary way for us to control what the model outputs is through the training data. It is crucial to use high quality data that represents your intentions for how the model should behave. If you don't want your model to spout conspiracy theories, don't include conspiracy theories as examples. If you don't want your model to be racially biased, make sure your training data doesn't include examples of racially biased text, including those where the bias is implicit.

However, today's ever-larger models require ever-more data for training and data scientists feel like they have to scrape the entire internet to feed their creations. For example, the training data used to train GPT-4, the model behind ChatGPT, was over 1 million gigabytes. This is the equivalent of one hundred times the information found in the Library of Congress!9 It is unfeasible to sift through this amount of data and remove anything we might find objectionable. As a consequence, all of the bias, hate-speech, conspiracy theories that are present on the internet also become part of the models.10

At the same time, we need a large amount of data so that models are able to find patterns and generalize what makes a dog a dog or discover the underling structure of a pop song. If you have too little training data, a model will just 'memorize' those specific examples and won't be able to handle inputs it has never seen before.11 It would be pretty useless to have an image classifier only recognize dogs in images that it saw during training. You want it to ‘know’ what dogs look like in general and be able to identify them across a range of new images. This generalization can only be achieved by training models on large and diverse datasets until the they learn to recognize patterns and create 'internal representations.'

Models within Models

Internal representations are abstract features or concepts inside AI models that help generate the final output. For example, an image classifier might use internal representations that recognize whiskers, paws, pointy ears to identify cats. An LLM (large language model) might have its internal representation of fairy tales ‘activated’ when promoted to continue a story beginning with 'Once upon a time…’

This process is similar to the cognitive shortcuts and predictive patterns that our brains learn over time, which simplify our daily lives and (hopefully) enhance decision making. When you imagine your mom's voice telling you to fold your laundry, you're using an internal representation of her to predict what she might say while looking at the sad state of your underwear drawer.

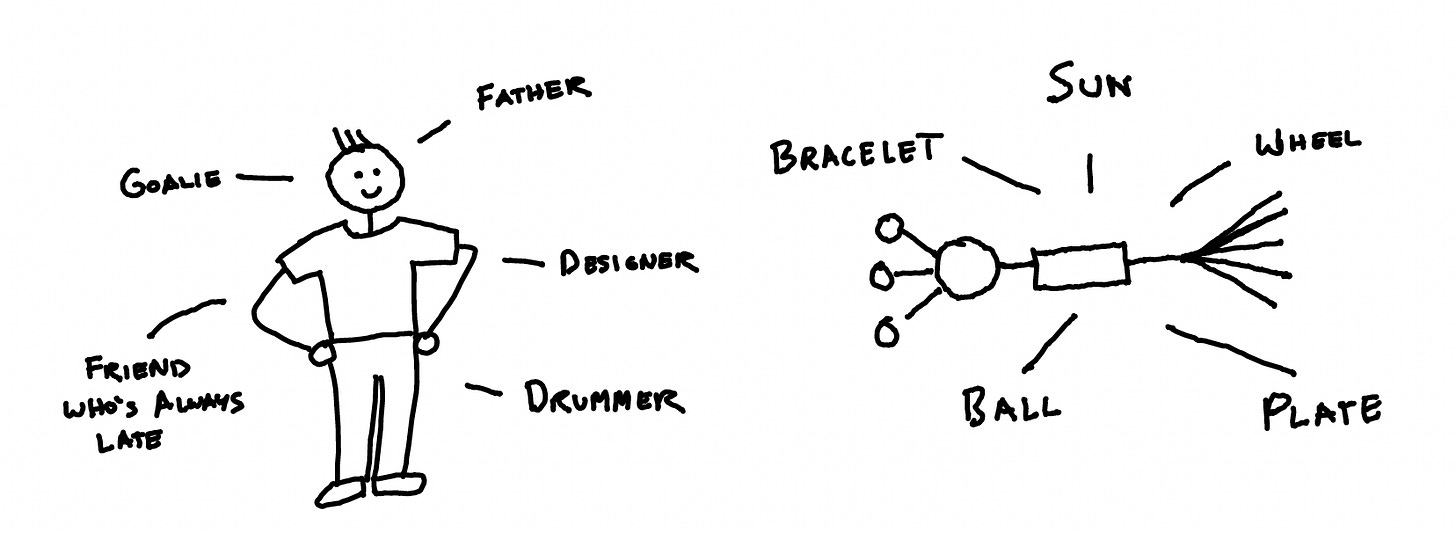

Just like you don't actually have a mini version of your mom living in your head, internal representations aren't standalone concepts that you can point to inside an AI model. Instead, they are groups of connected neurons that get triggered when a specific input is sent through the model.12 These groups can often overlap and intersect, and a single neuron is typically part of multiple inner representations inside a model.13

You can think of the relationship between neurons and internal representations like a person belonging to various groups and social contexts. An individual, despite having a consistent identity, plays a different role for their family than for their employer or their local football team. A neuron is much simpler, but how it behaves also changes depending on the internal representation 'group' that happens to be triggered at that moment.

These internal representations work together, each contributing a piece of ‘understanding’ that, when combined, allows the model to generalize its training data to a much larger set of possible inputs and outputs.14 An LLM that has a conceptual understanding of Bitcoin and a grasp of haiku structure can now create cryptocurrency-themed haikus. Larger models have more inner representations that often work together to give them capabilities beyond even what their creators intended!15

But how do models develop internal representations without being explicitly taught which patterns to recognize? The answer lies in compression. During training, a model's goal is to map inputs from the training set to the correct outputs. The more pairs they are able to map correctly, the better they score. The simplest way to achieve a perfect score would be to memorize every input and output pair in the training set. However, models are typically much smaller than the volume of their training data. They simply don't have enough memory to store every input and output they are shown. Instead, they have to find a way to ‘compress’ all of that data in a more efficient way.

When you compress data, you are turning it into a smaller form that can be unfolded later. One way to do this is to find an underlying rule and use it to derive the relevant data when its needed. For example, in the 1500s, sailors relied on bulky almanacs with long lists of planetary positions that were critical for navigation. They were hundreds of pages long and contained thousands of entries about the position of each planet for each day over a specific time period. Eventually, these books were replaced by Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion, which allowed you to derive planetary positions at any given time using three simple equations. In essence Kepler's Laws compressed hundreds of pages into just three lines of text.

When you ask an AI model to learn a very large data set, you are forcing it to discover these underlying rules and patterns, since its the only way it can successfully ‘compress’ all of the inputs and outputs that it saw during training.

Because the data we ask AI models to map is often much less regular and predictable than the motion of planets, internal representations aren't as simple and clean as Kepler's Laws. They are more like approximations and may represent things we don't have descriptions for or even recognize. Remember that during training, we didn't actually care about how the model was producing the right output, just that it did. And because of this, we don't really know what the internal representations of any AI models look like, only that they work in producing good enough outputs during training.

The 'Black Box'

If you open up an AI model to look for these internal representations, all you will see is the array of numbers that make it up. Unless you happen to be Cypher from the Matrix, its almost impossible to identify which of these numbers together make up a Shakespearean sonnet or the word 'vibe.' This is known as the 'black box' of AI, portraying the mystery of what's happening inside AI models when they produce an output.

This 'black box' is the aspect of AI that still feels like magic, even to experts. We understand all of the steps involved in getting AI to work: from setting up a model, to training it, to the process it follows when it produces output. What we don't get is the specifics of what it's doing when it's producing that output. Parents of teenagers must feel something similar. They bring them into existence and train them to be good human beings, but have no idea what's going on in their heads when they decide to get an eyebrow piercing.

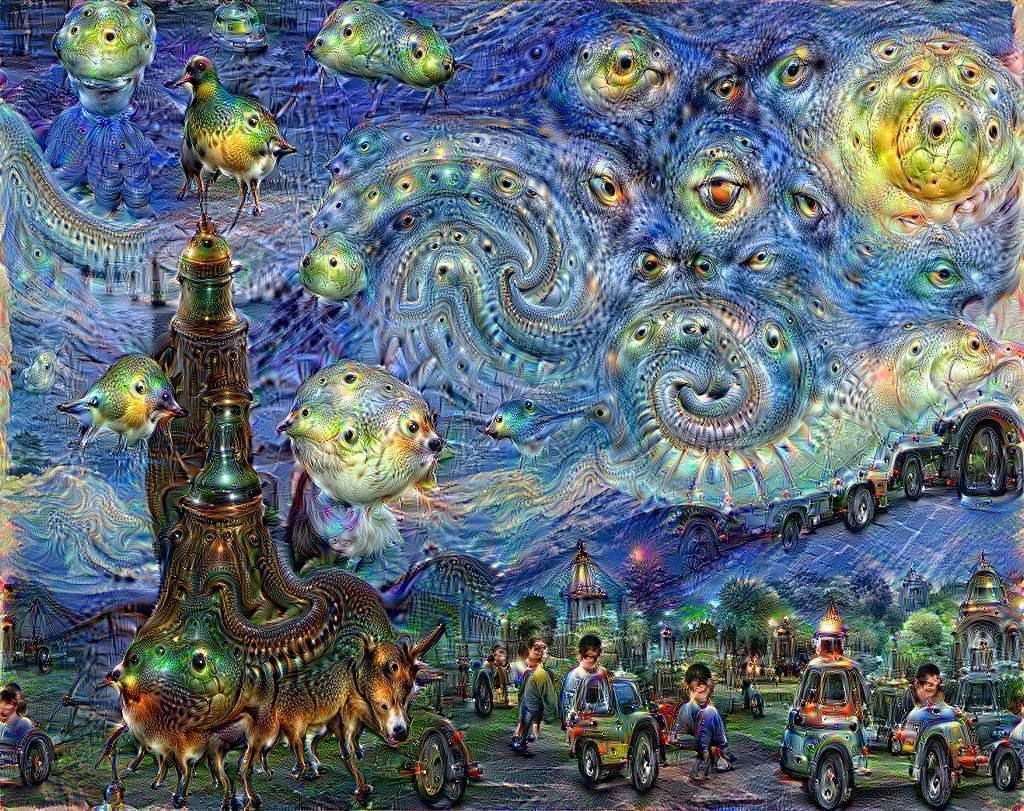

Engineers are working hard to crack the black box problem and one of the more interesting explorations into the mind of AI is a project called DeepDream, released by Google in 2015. To create DeepDream, engineers used a pre-trained image classification model which contained internal representations of specific labels it had learned to recognize such as dogs, cars, faces, etc. They setup this model so that instead of assigning a label to an image, the model would modify an image to fit a selected label better.

These labels are in fact internal representations inside the model. By modifying the original image to emphasize these internal representations, we can get a sense of what they might be. Here is what happens if we run The Starry Night through DeepDream.

As you can see, the output is quite surreal and gives a sense of how strange these internal representations are. Welcome to the weird and wonderful world inside AI models.

The Yin and Yang of Unpredictability

Due to their statistical, pattern-matching way of working and their 'black box' nature, AI models are inherently unpredictable. This unpredictability is what gives them their superpowers; they are able to handle complex and highly varied inputs thrown at them by complex and highly varied people and environments. Unlike traditional computers, you can give an LLM instructions in a thousand different ways and it will understand what you are trying to say. Diffusion models can generate a variety of unique images, even from the same prompt. Without this unpredictability, we wouldn't be questioning whether AI models have the capacity to be truly creative, something we previously felt certain was the last bastion of human intelligence.

At the same time, unpredictability can be frustrating (just ask anyone who's ever tried using a smart assistant to do anything) and even has the capacity for great harm. We can't fully trust outputs provided by AI models since we can't trace exactly how these outputs were produced. We aren't able to assess what biases AI models may have learned during training or how they manifest in outputs. And we don't know for sure whether the inherent goals of these models will align with what's best for humanity.

Fairy tales have taught us that magic can be both good and bad, we just need to learn how to harness it and use it in the right way.16 It's the same with AI. By understanding the principles of how models work, we can better grasp their strengths and weaknesses, be able to use them more effectively and also realize where they should not be used in the first place. I encourage you all to play around and explore the capabilities and boundaries of these models, especially as these boundaries are continuously expanding. Embrace their unpredictable nature, respect their limitations when it matters and enjoy getting to know this new and strange computational creature we have given birth to.

Epilogue

There are so many interesting concepts around AI that I didn't get a chance to cover with this article, partly because they might confuse rather than clarify things at this stage, and partly because I was afraid to put everything in an even longer article than this already is. If your curiosity about AI has been piqued, then stay tuned as I will be writing more on the topic in the near future. In the meantime, I will drop links from some amazing writers and content creators that dive deeper into specific aspects and provide a slightly different perspective on AI in general. As always, I would love to hear your thoughts and questions in the comments below.

Further Explorations

Here are some of my favorite resources on AI, from learning more about how it works, to what it means for our future and some fun experiments on the side.

The A-Z of AI: 30 terms you need to understand artificial intelligence: If you feel completely lost by all of the fancy terms surrounding AI, like 'compute', or 'instrumental convergence', then this BBC article provides a nice overview.

Large Language Models explained briefly: An explanation of how LLMs work in simple terms by one of my favorite youtube channels, 3Blue1Brown. The video is a great follow up from this article if you're curious specifically about how ChatGPT-esque models work. The visualizations give a great sense of the size of these models and reinforce some of the concepts we touched upon in this article

3Blue1Brown Neural Networks: If you liked the video above and want to understand the technical stuff involved with AI better overall, including some concepts I didn't go into detail in this article like 'gradient descent' and 'backpropagation', which both explain how an AI model adjusts its weights and biases to improve its outputs, this whole series is fantastic.

An entirely non-technical explanation of LLMs: If the 3Blue1Brown stuff feels too technical, then this explanation of LLMs, involving food and recipes, might be the way to go.

How AI Image Models Work: Same as above, only for image generation models. I actually like this analogy better than the LLM one.

What is ChatGPT Doing and Why Does it Work?: On the flip side, if you want to get slightly more technical and wayyyy more conceptual about how an LLM works, Stephen Wolfram's got you covered.

The AI Revolution: The Road to Superintelligence: The first part in a series on AI by Wait But Why which explains the different stages of AI, in terms of its capabilities and tries to assess timelines of when AGI (Artificial General Intelligence might happen).

Everything might change forever this century (or we'll go extinct): A video that explores what the consequences of AI might be in the coming century, for better or for worse.

We’re All Gonna Die with Eliezer Yudkowsky: If you want to know more about the 'for worse' option in terms of AI risk, or are not convinced by the doom-mongers saying the end is nigh, then this is the most thorough explanation of why AI might pose an existential risk for humanity. Also available as a podcast if you prefer it in audio form.

New Theory Cracks Open the Black Box of Deep Learning: The original article where I first learned about the 'compression' theory of how AI learns. If you're interested in the 'how' of AI, this one is a must read.

ChatGPT is a blurry JPEG of the Web: An op ed by one of my favorite sci-fi authors, Ted Chiang, where he builds on the 'compression' theory of AI and argues why this is not necessarily a good thing, especially for creativity

The Unpredictable Abilities Emerging From Large AI Models: An explanation of why AI might have unexpected emergent abilities, like ChatGPT knowing how to code. The article itself isn't super thorough but contains several links and follow ups if you're more curious.

New Theory Suggests Chatbots Can Understand Text: A follow up from the above, explaining how internal representations can be combined within LLMs to generate novel responses.

Building a Virtual Machine inside ChatGPT: Speaking of emergence, here is a fascinating experiment by an engineer that got ChatGPT to behave like a virtual computer, complete with internet connection.

Generative AI Space and the Mental Imagery of Alien Minds: 'Latent Space' is one of my favorite concepts around AI. I didn't get a chance to talk about it in this article, and perhaps I will in the future. Stephen Wolfram does a great job visually exploring this 'mental map' of all possible outputs and some of the weird things that lie in it.

Gemma Scope: A fun and accessible demo that shows DeepMind engineers' latest attempt at interpretability (aka cracking the "black box" of AI). I love how you can "crank up" certain internal representations to change the behavior of LLMs completely

Arguable paracetamol is a form of magic since we still don’t know how it works.

Strap something that is capable of making very large yet very controlled explosions at the end of a long pointy stick (commonly known as a rocket) and point it with the explody-bit facing down. This explosion creates a force that pushes your rocket in the opposite direction. Create a big enough explosion for long enough (controlling the explosion is the hard part) and your rocket might just reach space.

Coding languages themselves have been developed to allow us to give these very specific instructions to computers. Normal language is very imprecise. Think of the sentence, 'Put the pencil in the box on the table.' It can mean, 'put the pencil that is in the box on the table,' or 'put the pencil inside the box, which is on the table.' Human language has a lot assumptions and contextual information built into it and this is precisely why coding is so unnatural. We have to forgo this assumptive and intuitive way of speaking to give those precise instructions that computers demand. It’s much harder than it sounds, just ask these kids who tried getting their dad to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

There are some exceptions to this, such as when you increase the temperature in a large language model (LLM) to get a more random result. In an LLM, the output is produced sequentially, meaning that the model predicts one token (word), then predicts the most likely next token and so on and so forth. Increasing the temperature is the equivalent of adding some random noise to the selection process from the list of possible next tokens. The higher the temperature, the more likely it is that the LLM will not pick the highest probability output from the list but something further down. This is useful if you’re not looking for one correct output for the input and want some variety in exchange for sure-fire coherence.

There are cases where you train AI models without knowing what the correct answer is. These boil down to two categories. The first is unsupervised learning, where the data has some sort of natural structure to it and you allow AI models to discover these patterns on their own (This is primarily how LLMs are trained). The second is reinforcement learning, where you set up an environment for the model to act within and reward it for achieving certain goals (This is how AlphaGo was trained, with the reward being winning the game of Go).

I won't go into backpropagation in detail here. If you're curious, here is a slightly more mathematical but excellent overview by 3Blue1Brown.

If you try to look at what's happening in an AI model, all you will see is a bunch of numbers changing as the data passes through it. Here is a really good visualization of a hand-writing prediction model as it makes a prediction.

The Library of Congress is estimated to have around 170 million items, including books, recordings, photographs, maps, and manuscripts. If we assume an average of 6 MB per item, one million gigabytes could store the equivalent of about 100 times the entire Library of Congress.

Data scientists are trying to mitigate these effects with techniques like RLHF (Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback), where after the initial training, the AI model is further refined by outputting answers and having them scored by people who look out for any outputs that may have bias or potential for harm in them. But this seems like a band-aid and doesn't fully mitigate more subtle or hard to detect biases that might exist within the models, especially as they are used in contexts that aren't being tested for by these human trainers.

Data scientists typically call memorization ‘overfitting’, where an AI model knows its training data very well but produces bad results if the inputs deviate slightly from what it has seen before. This is similar to a student who has crammed for her exams by memorizing the course material rather than understanding the subject. If she sees something outside of what she has learned by rote, she isn't able to derive a good answer.

I like to think about the activation of an internal representation like a dog perking its ears up when it hears a certain sound. Its something a model has learned to pay attention to and ‘behave’ in a certain way if it recognize something similar in its input.

Here is a fantastic video explaining what’s happening inside a neural network and why it can be so difficult to figure out what these inner representations are.

Let's not confuse this 'generalization' of training data to mean that all internal representations are generic and high level. An LLM can learn some very specific pieces of information, such as George Washington's date of birth, through training. What we mean by generalization is that if it happens to see George Washington's date of birth ten times across its training, it creates an internal representation of it, rather than memorize each of those ten occurrences.

The fancy way of saying this is 'emergent capabilities'. Its when AI models start exhibiting behavior that its creators didn't explicitly teach during training. ChatGPT being able to code is an example of this.

I read this slowly over a few weeks and feel like I just got a minor degree.

I really enjoyed it. Thanks

Loved the article and the humor in it as well !